This is the fifth of five blog posts for British Science Week in which we address who we are, what we do and some of the challenges we face in using science to help understand, manage and conserve heritage.

Today’s challenge is resilience. Resilience is a term for how well something can respond to a difficulty and return to normal. Although many heritage sites and objects require protection and conservation from further damage, others are able to deal with whatever is thrown at them. This makes them resilient. Although many heritage buildings and sites have survived well and been resilient for many decades or centuries, some face new threats due a changing climate, air pollution and increasing visitor numbers. The goal of heritage conservation is to manage the change of objects and sites to make them more resilient – slowing down deterioration so that their values can be shared with future generations. If conservation goes wrong, heritage sites and objects can become less resilient. But doing nothing is usually not an option. The challenge for scientists and conservators is how best to manage change and improve the resilience of fragile, valued objects and sites.

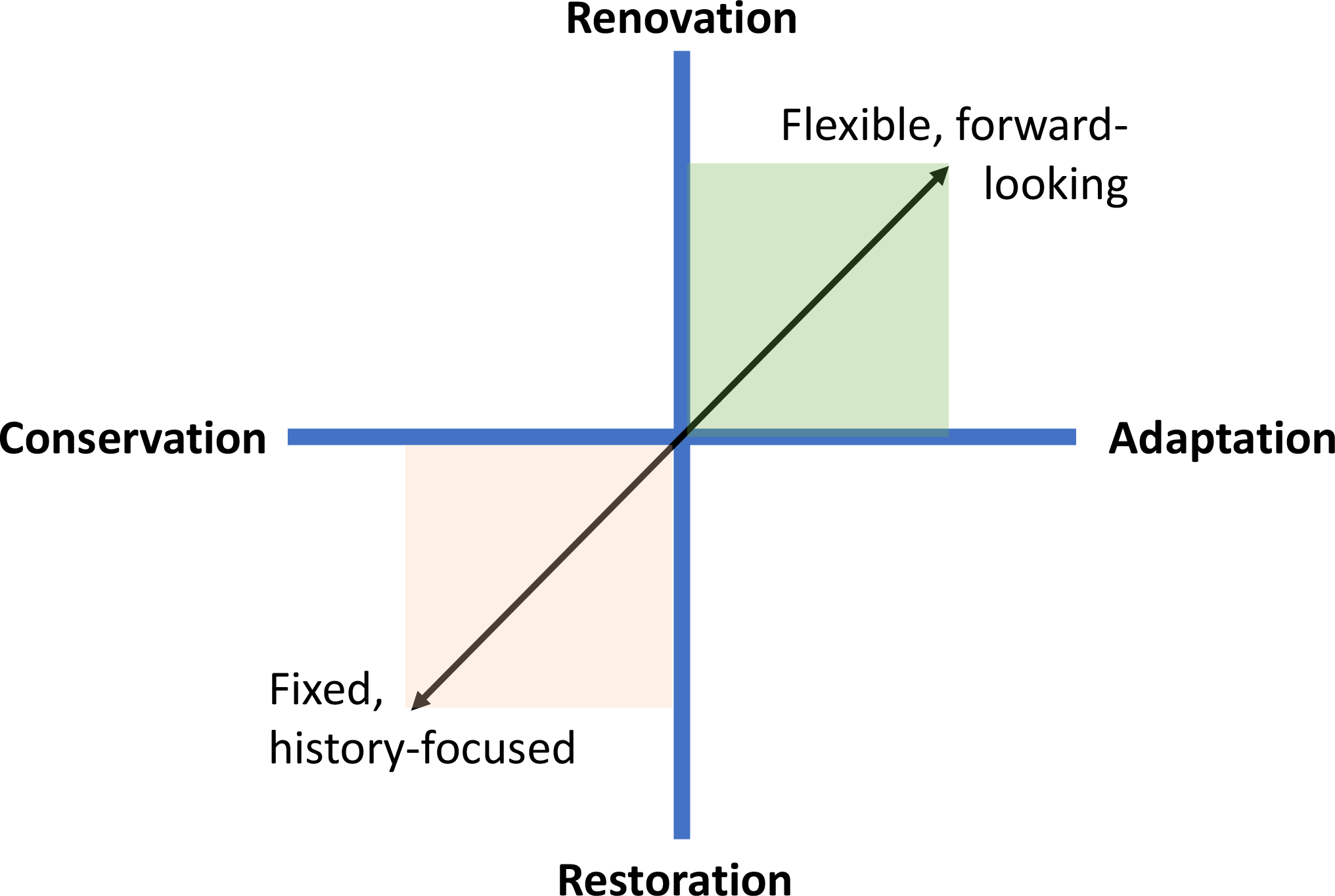

The graph above shows some different responses to this challenge using two axes. The horizontal axis depicts how much change is allowed (on the left-hand side the word ‘conservation’ implies very little change, whereas the word ‘adaptation’ on the right-hand side implies a lot of change. The vertical axis depicts what the end goal is – from ‘restoration’ at the bottom, which implies returning something to its former condition, to ‘renovation’ at the top, which implies creating something new but still valued. All these approaches can increase or decrease the resilience of heritage, depending on how they’re done. There is no right answer to what the best approach is – it depends on the characteristics of the specific object or site, what the people who value it want, and what is most possible. Although in OxRBL we are scientists and not practicing conservators, we have to think about these issues. Many of our projects focus on testing whether a conservation strategy will be successful in managing change and increasing the resilience of a particular site or object. But we also need to think about what people want the site or object to look like.

Conserving 1000-year-old walls: Martin at the Tower of London

Martin Michette

Martin Michette

Doctoral student in OxRBL

Martin studied architecture at the University of Bath and building conservation at the Potsdam University of Applied Science before spending several years in practice.

He now works on how best to conserve fragile Reigate Stone walls at the Tower of London.

Martin is really lucky to be carrying out research at the Tower of London in collaboration with Historic Royal Palaces (the site manager). The medieval Reigate Stone at the Tower of London is often quite fragile, and decades of work has gone into trying various conservation methods to slow down the decay and increase its resilience. Most have only been partly successful at best. Martin’s project aims to explore new conservation approaches that might be more flexible and forward-looking while still conserving the important heritage values of the Tower.