This is the fourth of five blog posts for British Science Week in which we address who we are, what we do and some of the challenges we face in using science to help understand, manage and conserve heritage.

Today’s challenge is value. By definition, heritage objects and sites are things of great value to the people who identify them as part of their cultural heritage. The more valued an object or site, the less likely scientists are able to touch it, take samples or interfere with it in any way. This poses a real challenge for scientists who are used to collecting samples from objects to find out more about them. For example, geologists usually use hammers to chip off parts of a cliff face to identify what the rocks are – this would be completely unacceptable at somewhere like Stonehenge, where taking even the tiniest of samples is challenging and requires high-level permission. Luckily, there are several ways we can study valuable things without damaging them as we illustrate below.

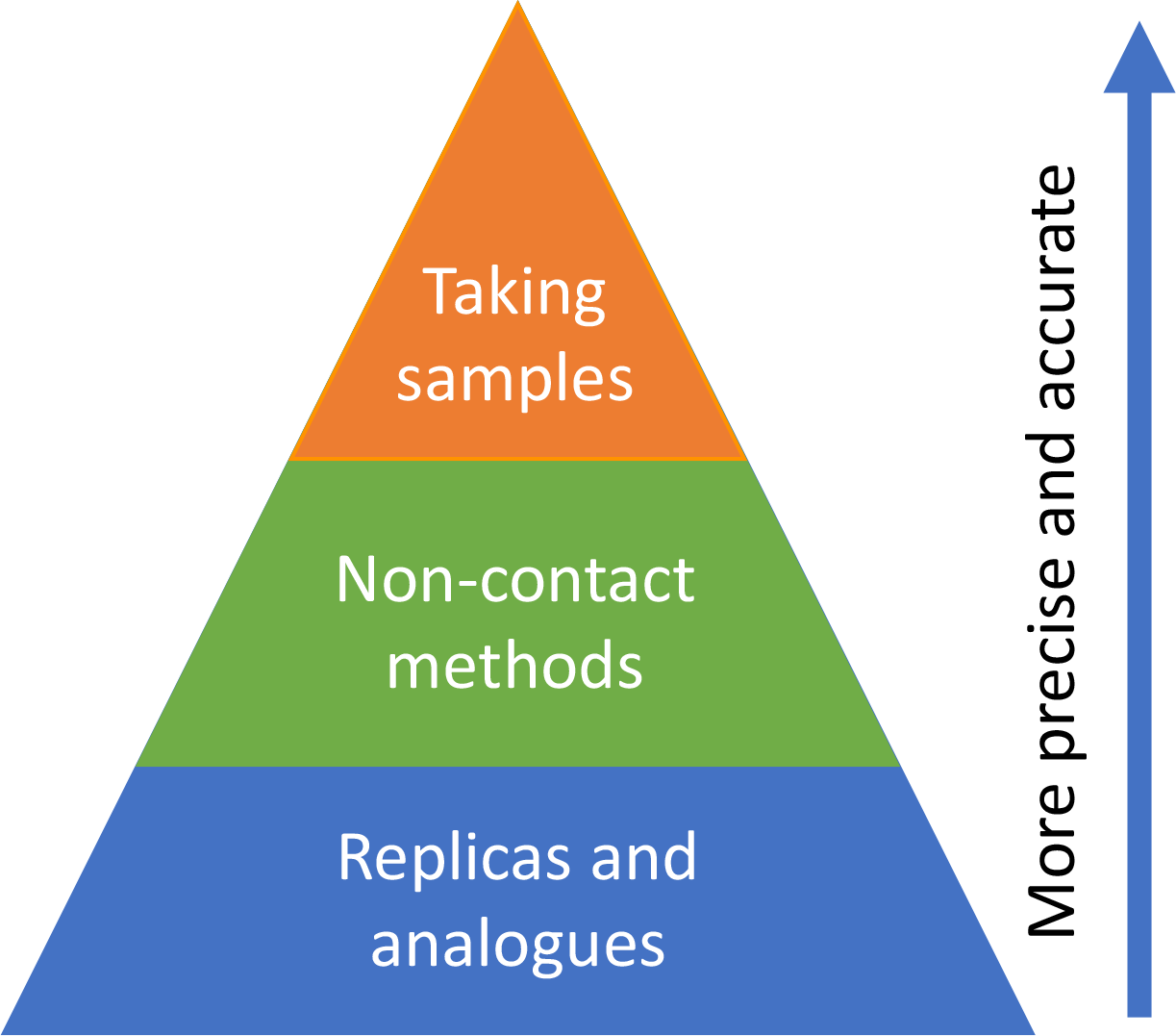

At the top of the triangle we can, in some cases, get permission to take very small samples from heritage objects and sites. Even very tiny flakes of a deteriorating surface can be used to identify what is causing the deterioration. But such small samples can usually only be analysed with high-tech, expensive scientific equipment in specialised labs. These can only tell us certain things about the heritage site or building we are interested in as a whole. In the middle of the triangle are non-contact methods that we can use on heritage objects or sites to diagnose problems or monitor change over time. These non-contact methods are usually relatively inexpensive and easy to use but give less precise and accurate information than the high-tech sample-based methods. Access to the heritage object or site can a limiting factor for this type of research. At the bottom of the triangle are some of the most commonly used approaches, involving replica or analogue samples. Essentially, this means making our own objects that are as similar to the real heritage object as possible. As you can imagine, there are lots of challenges to making realistic replicas of many heritage objects (especially very large, complex and old ones!).

Studying without touching: Scott and his wet walls

Dr Scott Orr

Lecturer in Heritage Data Science, University College London and Honorary Research Associate, OxRBL.

Scott studied chemical and environmental engineering at the University of Toronto.

He works on climatic impacts on heritage buildings.

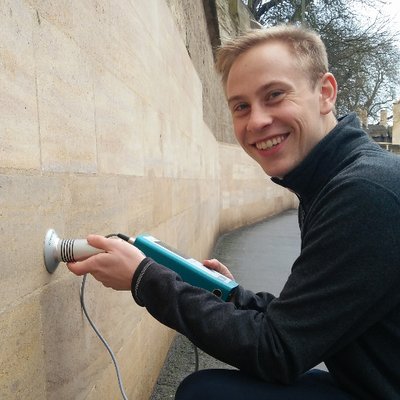

Scott is interested in why walls in historic buildings get wet and what damage that wetness can cause to the buildings, their contents and inhabitants. Faced with the challenge of not being able to drill holes into historic walls, Scott has worked with many non-destructive testing methods which can be used to ‘see inside walls’ without damaging them at all. One of his preferred methods is a hand-held system that measures microwave reflections by simply placing a sensor on the surface. This allows him to investigate how wet walls are at different depths.

Making minerals: Kathryn and museum collections

Kathryn Royce

Kathryn Royce

Doctoral student in OxRBL

Kathryn did an undergraduate degree in conservation science at Cardiff University.

She now studies the deterioration and conservation of mineral collections in association with the National Museum of Wales.

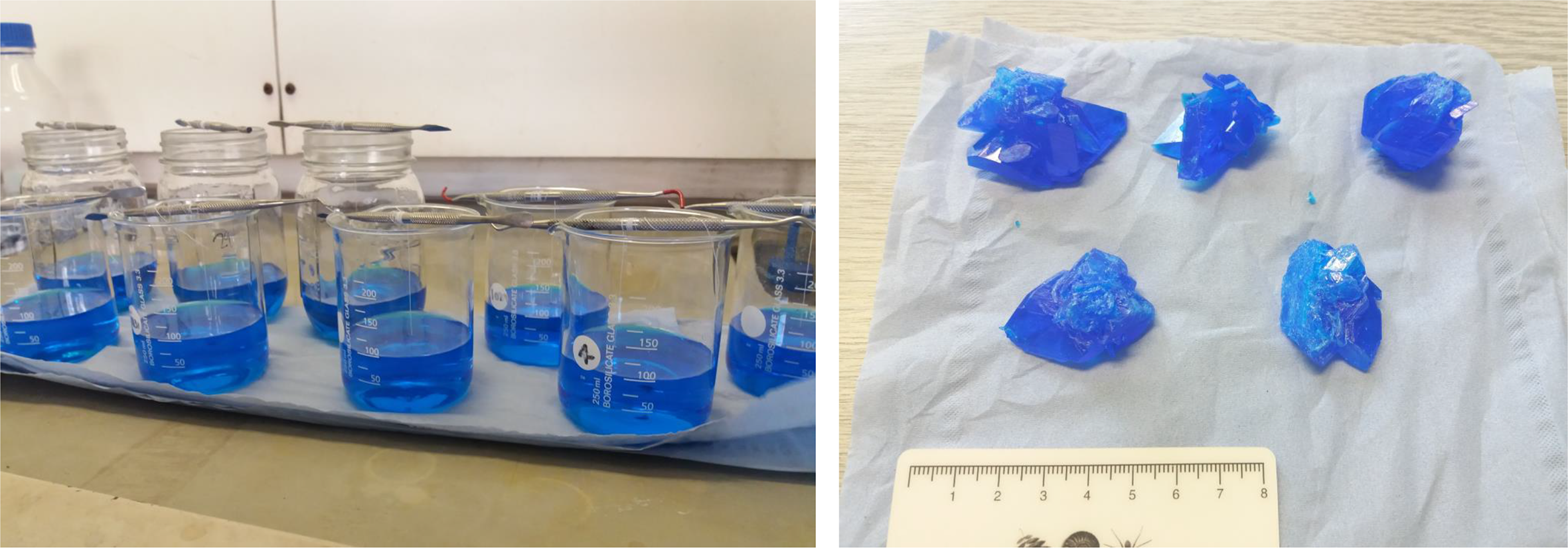

To cope with the challenge of not being able to take samples of valuable minerals stored in museums, Kathryn has decided to ‘grow her own’. Using the right chemicals under controlled conditions, it is possible to grow crystals of some minerals that look much like the ones on display in museums. The benefits of ‘growing your own’ are that you can make many replicas and then carry out many experiments on them. But how realistic are these ‘home grown’ minerals to the valuable ones on display (which might have been collected years ago from faraway places)?

Growing Chalcanthanite crystals in the lab