This is the third of five blog posts for British Science Week in which we address who we are, what we do and some of the challenges we face in using science to help understand, manage and conserve heritage.

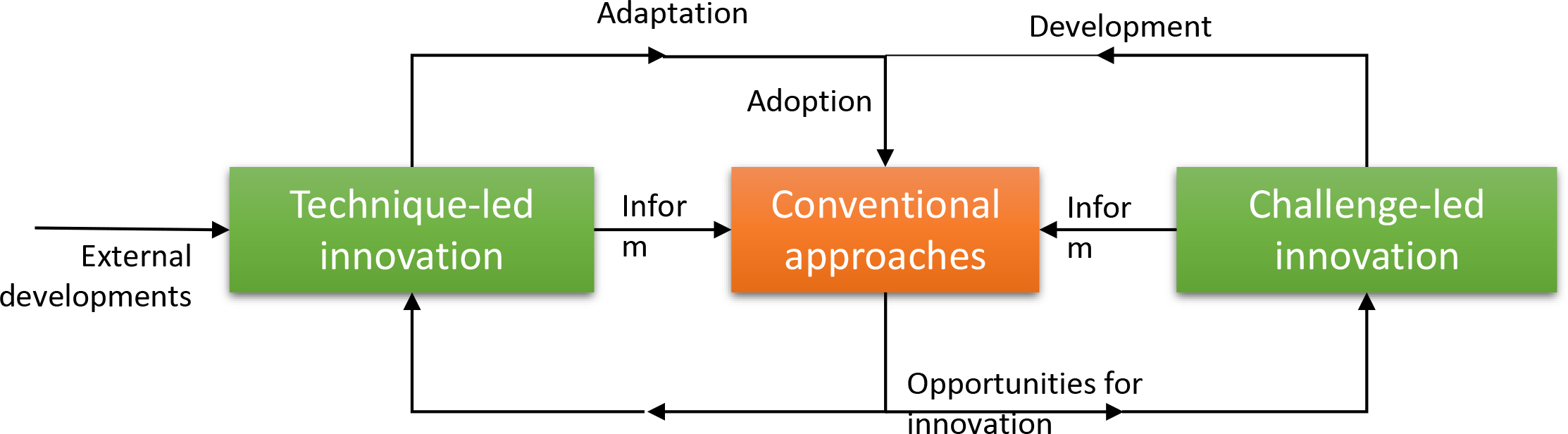

Today’s challenge is innovation. All scientific researchers aim to do something innovative, whether that’s by making some hugely important discovery or by developing a new way of making observations (or perhaps combining the two). Often when you are actually in the lab, in the field, or staring into your computer, it feels as though you are a long way from doing anything innovative at all. It’s easy to get disheartened. In OxRBL, we have found the illustration below a useful way of picturing the sources of innovation and how they are interrelated within the ‘cycle of innovation’.

Innovation can come from the scientific techniques we deploy (on the left-hand side of the diagram) or from the challenges that a heritage site or object might throw at us (on the right-hand side of the diagram). The black arrows illustrate the ways in which such innovations inform conventional approaches and which can often lead to new developments, adaptations and further innovations. Different sciences fit in different places on the diagram. For example, much engineering is challenge-led, while many parts of ‘pure’ sciences – like chemistry and physics – are technique-led. The science we do for heritage is really in the middle of the diagram.

Technique-led innovation: Dáire in the lab with lasers

Dáire Browne

Dáire Browne

Doctoral student in OxRBL

She studied chemistry in Oxford as an undergraduate and now works with OxRBL and the Ritchie Group in the Physical and Theoretical Chemistry Lab.

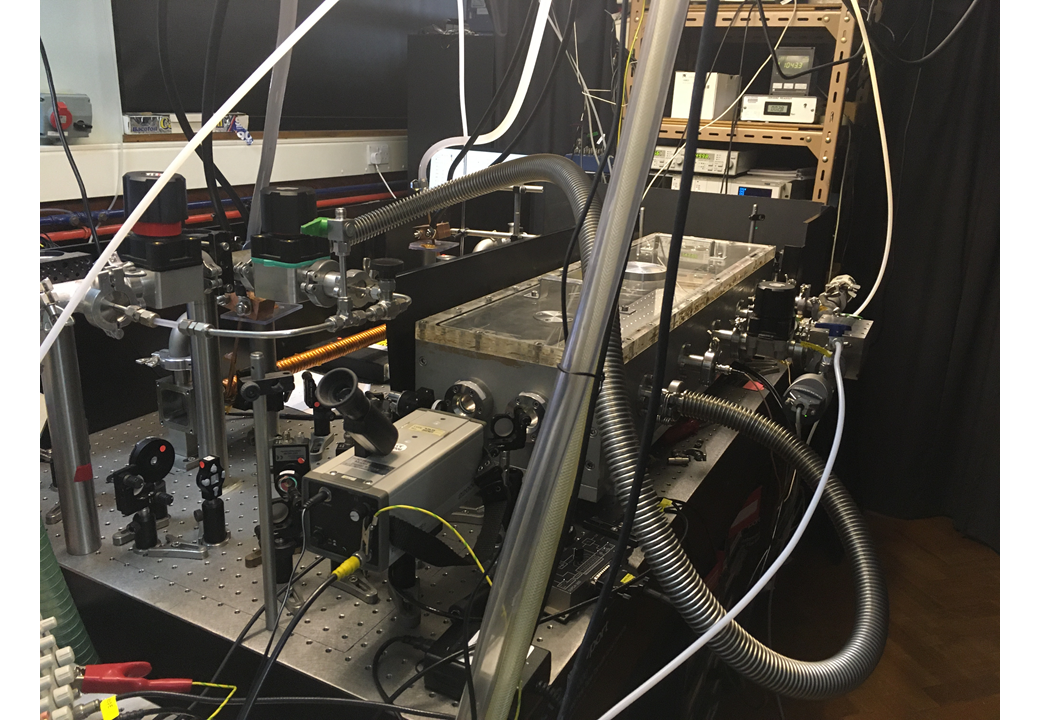

Dáire’s research is firmly based on technological innovation. She is currently developing a new instrument based on laser absorption spectroscopy to measure water and pollutant gases coming in and out of limestone. This instrument should provide a novel and accurate way of monitoring how some of the key agents of deterioration interact with the surfaces of heritage buildings. Dáire will spend most of her time in the lab, but we hope that one day she will be able to apply her technique to a number of different heritage challenges.

Dáire’s cavity ring-down laser spectroscopy system ready to start work in the lab (Ritchie group in the Physical and Theoretical Chemistry Laboratory, 2020)

Challenge-led innovation: Richard and the mechanical foot

Richard Grove

Richard Grove

Doctoral student in OxRBL

Richard studied archaeology and landscape studies at the University of Worcester and historic conservation at Birmingham. He ran his own business before coming to Oxford.

Richard’s research aims to develop a ‘best practice’ method to test whether conservation treatments on crumbling historic sandstone surfaces have been successful. His challenge has been to find the best techniques available that can be used in the field or in the lab. He is particularly interested in the impact of visitors walking on vulnerable surfaces. Thanks to a chance conversation at a party, he found a company that tests footwear (Satra) who have been able to run some experiments for him using their Pedatron tester – a challenge-led, novel application of a technique usually deployed to assess the lifespan of walking boots.